Optical Tweezers at the limits

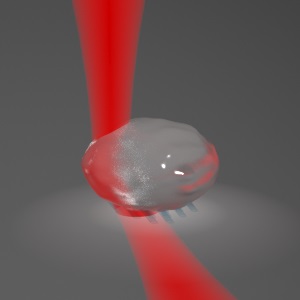

Optical Trapping (OT) is a well-established method for manipulating nanometre to micrometre-scale transparent objects. It uses an optical force known as the gradient force to trap and hold tiny particles in a focused laser beam.

A highly focused laser beam creates an intensity gradient near its focal point sufficiently large to give rise to forces on transparent objects with different refractive indices to their surroundings. The size of particles which they can trap (micro and nano) and the range of forces they exert (piconewto, pN) make them an ideal tool for exploration of a variety of fields such as Biomedical research, Cell Biology, Statistical thermodynamics and colloid science. OT provides one of the most sensitive ways to measure the forces which are present in the microscopic world. Birefringent materials like Vaterite can be used to create tiny micro-rotators which can be used as probes.However the exertion of stronger forces, and the manipulation of larger objects remains challenging. Furthermore, trapping objects in vivo, especially at depth, is difficult because of the scattering and power loss that results from passage through biological tissue.

The most common optical trap shape is a focussed Gaussian beam. A Gaussian beam can be used to grab particles, and for non-spherical or birefringent particles, the polarisation of the beam can be used to align the particle. For rotating particles, beams with circular polarisation or optical orbital angular momentum can be used. In order to control the orientation of particles more precily we can explore different shaped traps. Recently we explored the use of annular beam optical tweezers (Lenton et al., 2020) with slowly varying position for the orientation of E coli. Although we found these traps are not very suitable for orientation of E coli in water, they may be useful for orientation or trapping of rod-shaped spores in air or vacuum (in a setup similar to (Pan et al., 2019)).

Recent results include:

2020

Orientation of swimming cells with annular beam optical tweezers

Lenton, I. C. D., Armstrong, D. J., Stilgoe, A. B., Nieminen, T. A., & Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H. (2020). Opt. Commun., 459, 124864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2019.124864'

2019

Optical-trapping of particles in air using parabolic reflectors and a hollow laser beam

Pan, Y.-L., Kalume, A., Lenton, I. C. D., Nieminen, T. A., Stilgoe, A. B., Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H., Beresnev, L. A., Wang, C., & Santarpia, J. L. (2019). Opt. Express, 27(23), 33061–33069. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.27.033061'

2017

Optical trapping of otoliths drives vestibular behaviours in larval zebrafish

Favre-Bulle, I. A., Stilgoe, A. B., Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H., & Scott, E. K. (2017). Nature Communications, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-00713-2'

Ultrasensitive rotating photonic probes for complex biological systems

Zhang, S., Gibson, L. J., Stilgoe, A. B., Favre-Bulle, I. A., Nieminen, T. A., & Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H. (2017). Optica, 4(9), 1103. https://doi.org/10.1364/optica.4.001103'

2015

Scattering of sculpted light in intact brain tissue, with implications for optogenetics

Favre-Bulle, I. A., Preece, D., Nieminen, T. A., Heap, L. A., Scott, E. K., & Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H. (2015). Scientific Reports, 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11501'

2013

Spatially-resolved rotational microrheology with an optically-trapped sphere

Bennett, J. S., Gibson, L. J., Kelly, R. M., Brousse, E., Baudisch, B., Preece, D., Nieminen, T. A., Nicholson, T., Heckenberg, N. R., & Rubinsztein-Dunlop, H. (2013). Scientific Reports, 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01759'